To The Teacher:

In the United States, we believe that each person has one vote and that each vote counts equally among all other votes. However, gerrymandering—the practice of drawing district lines for a political advantage—ensures that not all votes contribute equally to election outcomes. Particularly in the past decade, advanced computing and data gathering has turned the art of manipulating district borders into a science. And using this science, a particular party can be all but guaranteed a win on election day in a given area.

Advocates for fairer elections argue that gerrymandering harms democracy in the United States in three ways: it decreases the value of some people’s votes while over-valuing other people’s votes, it cuts down on the number of competitive elections, and it decreases the incentive for politicians to compromise, thereby increasing partisanship and gridlock.

This lesson consists of two readings. The first reading explains what gerrymandering is and why it is a problem for democracy in the United States. The second reading looks at recent attempts to combat gerrymandering, particularly court challenges in California, Wisconsin, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Questions for discussion follow each reading.

Reading One:

What Is Gerrymandering and Why Is it a Problem?

In the United States, we believe that we each person has one vote and that each vote counts equally among all other votes. However, gerrymandering—the practice of drawing district lines for a political advantage—ensures that not all votes contribute equally to election outcomes. Particularly in the past decade, advanced computing and data gathering has turned the art of manipulating district borders into a science. And using this science, a particular party can be all but guaranteed a win on election day in a given area.

If a state or city’s population consistently votes 60 percent for one party over another, you might expect that the majority of elected officials in that area would be from the leading party. However, through gerrymandering, district boundaries can be drawn in such a way that the minority party wins a greater number of seats.

As mathematics professor and author Jordan Ellenberg wrote in a New York Times article published in October 6, 2017, “About as many Democrats live in Wisconsin as Republicans do. But you wouldn’t know it from the Wisconsin State Assembly, where Republicans hold 65 percent of the seats, a bigger majority than Republican legislators enjoy in conservative states like Texas and Kentucky.”

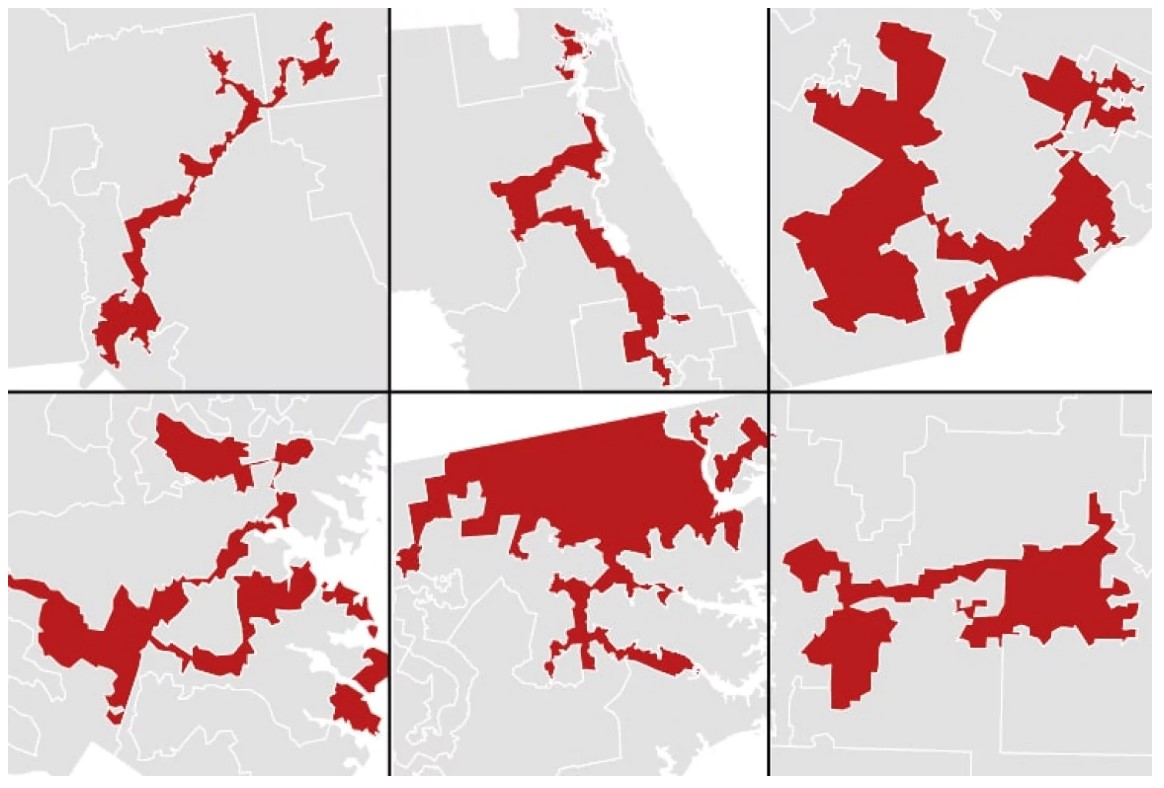

One might think that a district for a U.S. congressperson, for example, should follow already established geographical lines—such as the borders of a county or a division created by a river. However, gerrymandered district lines can be elaborately contorted so as to include more people likely to vote for one party and less for another.

The following diagram, from the Washington Post, shows some of the most extreme examples of congressional district gerrymandering across the country. In each example, the districts jump across established geographical lines and end up taking bizarre shapes that serve no purpose other than to increase partisan advantage.

Gerrymandering is hardly a new problem. Politicians have engaged in it for hundreds of years. Political scientist Brian Klaas described the term’s history in a February 10, 2017, article in the Washington Post:

The word ‘gerrymander’ comes from an 1812 political cartoon drawn to parody Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry’s re-drawn senate districts. The cartoon depicts one of the bizarrely shaped districts in the contorted form of a fork-tongued salamander. Since 1812, gerrymandering has been increasingly used as a tool to divide and distort the electorate. More often than not, state legislatures are tasked with drawing district maps, allowing the electoral foxes to draw and defend their henhouse districts.

Controversy around gerrymandering often comes down to three main issues. Fair elections advocates argue that gerrymandering: 1) decreases the value of some people’s votes while over-valuing other people’s votes; 2) cuts down on the number of competitive elections; and 3) decreases incentive for politicians to compromise.

As Klaas further argues, gerrymandering has resulted in uncompetitive elections across much of the country:

Last year [in 2016], only 17 seats out of 435 races were decided by a margin of 5 percent or less. Just 33 seats in total were decided by a margin of 10 percent or less. In other words, more than 9 out of 10 House races were landslides where the campaign was a foregone conclusion before ballots were even cast. In 2016, there were no truly competitive Congressional races in 42 of the 50 states.

While gerrymandering has long existed, evolving technology has dramatically changed how the practice affects elections. High-powered computers and access to demographic and voting data records allow politicians to predict how small changes to districting lines might alter electoral outcomes. As Ellenberg argues in the New York Times:

Gerrymandering used to be an art, but advanced computation has made it a science. Wisconsin’s Republican legislators, after their victory in the census year of 2010, tried out map after map, tweak after tweak. They ran each potential map through computer algorithms that tested its performance in a wide range of political climates. The map they adopted is precisely engineered to assure Republican control in all but the most extreme circumstances.

In a gerrymandered map, you concentrate opposing voters in a few districts where you lose big, and win the rest by modest margins.... A new paper by a team of scientists at Duke paints a startling picture of the way the Wisconsin district map protects Republicans from risk…. To gain control of the State Assembly, the authors estimate, Wisconsin Democrats would have to beat Republicans by 8 to 10 points, a margin rarely achieved in statewide elections by either party in this evenly split state. As a mathematician, I’m impressed. As a Wisconsin voter, I feel a little ill.

As gerrymandering has grown ever more sophisticated, opponents of the practice have stepped up their efforts to challenge it. This has resulted in a number of cases that are now working their way through the courts.

For Discussion

- How much of the material in this reading was new to you, and how much was already familiar? Do you have any questions about what you read?

- According to the reading, what is gerrymandering, and what are its impacts on the U.S. political process?

- According to the reading, why is gerrymandering a more serious problem now than in the past?

- Fair elections advocates make three main arguments about why gerrymandering is harmful. Do any of those stand out to you as important? Can you think of other arguments for or against gerrymandering?

- Has your congressional district been gerrymandered? If so, in whose interest were the lines drawn? If you don’t know, how might you find out?

Reading Two:

Challenging Gerrymandering in Court

As gerrymandering has become more mathematically sophisticated, fair elections advocates are challenging the practice in both state and federal courts. Recent cases in California, Wisconsin, Maryland, and Pennsylvania against partisan gerrymandering have contributed to wave of highly partisan gerrymandered maps being overturned across the country.

In a February 22, 2018, article for the Los Angeles Times, the newspaper’s editorial board described court cases against gerrymandering in several states:

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to decide two gerrymandering cases within the next few months. The court already aided the cause of reform with a 2015 ruling upholding the right of states to entrust the drawing of congressional district lines to independent commissions, as California does. But the cases before the court this term provide an opportunity for the justices to go dramatically further and rule that some gerrymanders are so extreme that they violate the U.S. Constitution.

The first case, which was argued last October, involves a Republican-friendly map for the Wisconsin Assembly. The second, which will be argued March 28, focuses on a map fashioned by Democrats that allowed their party to capture a historically Republican seat in Maryland's House delegation.

Looming over both cases is a 1986 Supreme Court decision holding that partisan gerrymandering could violate the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause if it intentionally and effectively discriminated against an identifiable political group, such as members of a political party....

Lower courts have cited both the 14th and the 1st Amendment to the Constitution in upholding challenges to gerrymandered maps. As the Los Angeles Times further notes:

In striking down the Wisconsin map, a three-judge federal court said that the U.S. Constitution was violated if a redistricting plan is "intended to place a severe impediment on the effectiveness of the votes of individual citizens on the basis of their political affiliation," has that effect, and "cannot be justified on other, legitimate legislative grounds." The judges relied not only on the Equal Protection Clause but also the free-speech protections of the 1st Amendment.

The 1st Amendment is at the center of an argument for lawyers challenging the Maryland map, which was designed by Democrats to eliminate a GOP-friendly seat long held by Republican Rep. Roscoe Bartlett. In their petition to the Supreme Court, the lawyers representing Republican voters argue that "citizens enjoy a 1st Amendment right not to be burdened or penalized for their voting history, their association with a political party or their expression of political views."

In Pennsylvania, fair election advocates have based their case against a highly gerrymandered districting map on the state constitution. As law professor David S. Cohen wrote in a January 23, 2018 in Rolling Stone:

Yesterday, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court gave a big boost to [the effort to reduce partisan gerrymandering] by ruling the state's congressional map was unconstitutionally gerrymandered. Better yet, the ruling should be final and unreviewable by the U.S. Supreme Court.

This was one of the most closely watched gerrymandering cases in the country. In every election since the state map was redrawn by Republicans in 2011, Republicans have won the same 13 of the state's 18 congressional districts, despite Pennsylvania voting for President Obama in 2012 by over 5 percent and only barely favoring President Trump in 2016 by less than 1 percent.

The basic argument in the case is this: a state that is so evenly split (if not slightly favoring Democrats) can only have a congressional delegation so strongly Republican if the districts were gerrymandered in a way to intentionally diminish Democratic voices.

Yesterday, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court agreed, ordering the legislature to re-draw the districts in a fair manner….

What makes this case so important is that it was decided by a state supreme court on the basis of state constitutional law. Why's this important? Because when a state supreme court makes a decision on the basis of its own state's law, the U.S. Supreme Court doesn't review the case. It's as if a different country's court system decided a case under that country's law. The U.S. Supreme Court would have no say. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court made this clear yesterday saying explicitly that it reached its conclusion on the "sole basis" of the state constitution.

Projections based on past voting records suggest that the Pennsylvania’s new districts, drawn by the court since its initial ruling, could result in more contested elections and dramatically swing the political balance of the state in coming elections.

While the court’s decision in the redrawing of the Pennsylvania districts is a significant step towards more fair elections in the state, gerrymandering remains a significant problem. Political scientists warn that, if the Supreme Court reverses the lower court ruling in the case concerning Wisconsin’s political maps, we could witness a new wave of highly partisan gerrymandering when states draw new districts in 2020.

For Discussion

- How much of the material in this reading was new to you, and how much was already familiar? Do you have any questions about what you read?

- As the reading notes, some court challenges to gerrymandering are based on the 14th Amendment, which states that the U.S. government may not “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” What do you think of this argument? Do you think a given group living in a gerrymandered district might not be receiving equal protection under the law?

- Another approach is to argue against gerrymandering using the 1st Amendment, which states that Congress shall make no law “abridging the freedom of speech.” Would you consider gerrymandering a violation of free speech? Why or why not? Do you think this is a stronger or a weaker argument than using the 14th Amendment?

- Some opponents of gerrymandering are concerned that the practice is used to give one party the advantage over another. However, others are concerned that there are simply too many “safe” seats for politicians and too few elections that are truly contested. In a state that was divided evenly between supporters of two parties, do you think it would be fair if there were one “safe” seat that each party was heavily favored to win? Or do you think it would be preferable to have two districts with roughly the same numbers of supporters from each party, so that both elections were more hotly contested? What would be some of the pros and cons of each system?

- How might everyday residents who are concerned about gerrymandering in their district (or anywhere) effectively advocate for their views?

—Research assistance provided by Ryan Leitner.